Canada’s Leading Gold and Silver Dealer

Border Gold Corp. (BGC) is one of Canada’s leading gold, silver, and precious metal dealers. Over the years BGC has become one of the largest Royal Canadian Mint direct distributor in Canada. Under the leadership and ownership of Michael Levy, BGC continues to provide clients with the best customer experience in the industry.

BGC is able to offer its clients a variety of investment bullion products. Our relationship with the Royal Canadian Mint and other large-scale distributors allows us to consistently offer clients among the best pricing in the industry. If you’re looking to buy gold and silver, or sell it, we can help. Learn more about our services here.

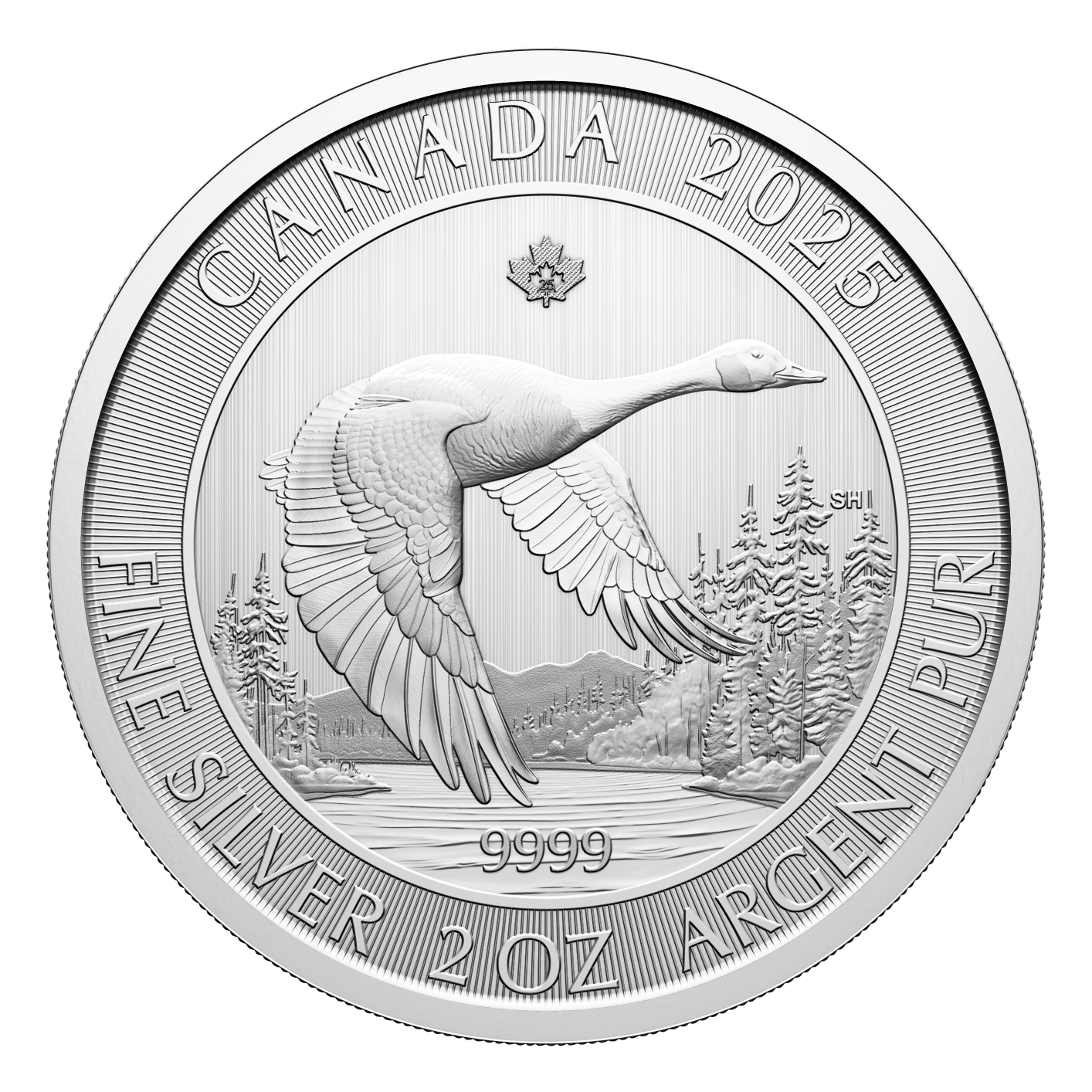

Featured Silver

| 1 - 99 | $38.43 |

| 100 - 499 | $38.38 |

| 500+ | $38.33 |

| 1 - 49 | $40.38 |

| 50 - 99 | $40.13 |

| 100 - 499 | $39.98 |

| 500 - 1999 | $39.93 |

| 2000+ | $39.88 |

| 1 - 13 | $81.15 |

| 14 - 27 | $80.95 |

| 28 - 279 | $80.85 |

| 280+ | $80.75 |

| 1 - 9 | $392.76 |

| 10 - 49 | $392.26 |

| 50 - 99 | $391.76 |

| 100+ | $391.26 |

| 1 - 9 | $3,862.60 |

| 10 - 49 | $3,857.60 |

| 50+ | $3,852.60 |

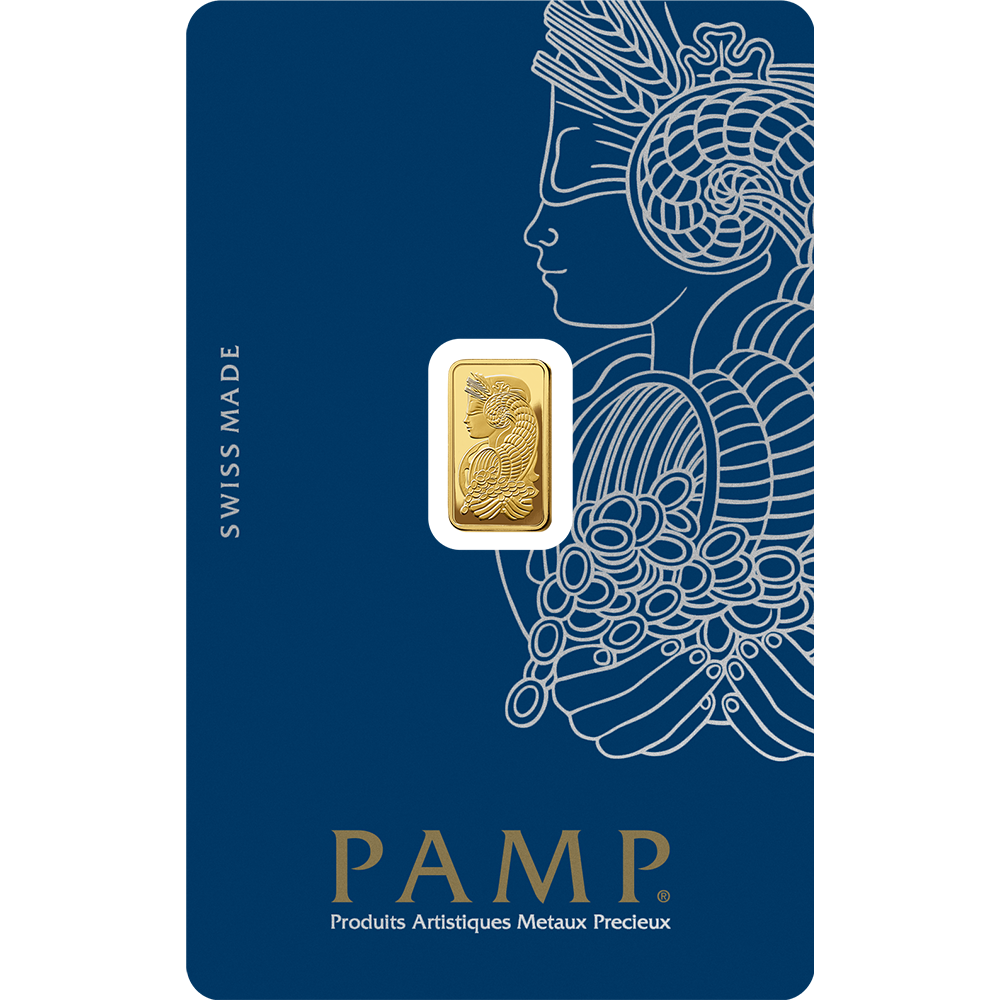

Featured Gold

| 1 - 9 | $3,355.12 |

| 10 - 49 | $3,350.12 |

| 50+ | $3,345.12 |

| 1+ | $142.80 |

| 1 - 9 | $371.78 |

| 10+ | $368.49 |

| 1 - 24 | $1,101.20 |

| 25+ | $1,100.56 |

| 1 - 9 | $1,751.99 |

| 10+ | $1,743.76 |

STORAGE SOLUTIONS

Whether securing storage of a regular purchase or contributing and holding physical metal in a RRSP or alternative savings account, we can suggest solutions that will cater specifically to you. The benefits of having Border Gold play a role in your storage solution is the guarantee and ease of liquidity when it comes time to sell part of, or all your physical assets.

Like any other purchase, clients buy the metal from Border Gold, and then receive notification of prompt delivery to your storage locations.